The Dutchman is Rated R by Motion Picture Rating (MPA) for sexual content, language and brief violence.

Andre Gaines’ contemporary reimagining of The Dutchman, drawn from Amiri Baraka’s incendiary 1964 play, is nothing if not audacious. It takes big, risky swings sometimes admirably so, often less successfully and while many of those gambits don’t quite land, there’s an undeniable nerve behind them. That boldness alone makes the film an intriguing case study in what happens when a volatile stage work is dragged, sometimes kicking and screaming, into a modern cinematic context. Baraka’s original play, written in the immediate aftermath of Malcolm X’s assassination, staged a brutal, claustrophobic confrontation: a white woman corners a Black man on a New York subway, weaponizing seduction and contempt to probe the raw fault lines between white and Black America, and the psychic turmoil Black men were being forced to navigate within themselves.

You don’t have to know Baraka’s work going in, though familiarity certainly deepens the experience. Gaines and co-writer Qasim Basir lean heavily into a self-aware, almost meta framework, treating Dutchman not just as source material but as an object that exists inside the film’s own universe. The play is both ancestor and specter here, hovering over the story even as a parallel narrative plays out. In theory, any attempt to update Baraka’s work must grapple with the shifting political landscape, and The Dutchman tries to justify its departures leaving the subway car behind at times, expanding into other spaces while still clinging tightly to the original’s thematic spine.

That strategy cuts both ways. On one hand, the film rarely introduces genuinely new political insights; it circles ideas that have already been articulated, often more sharply, decades ago. On the other hand, its refusal to sever ties with a 60-year-old text becomes its own artistic question. Why revisit this story now, and why in this way? The movie never quite answers that, but there’s a faint, melancholy suggestion that something meaningful is buried just beneath its surface. The tragedy is that the film only ever scratches at it, never digging deep enough to unearth whatever truth it’s straining toward.

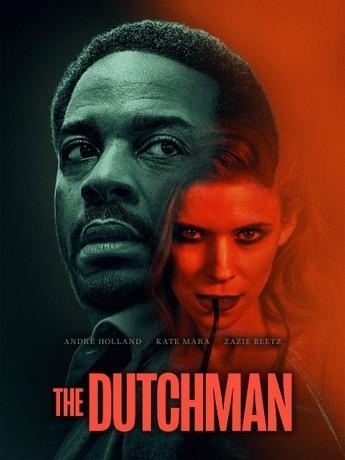

The story centers on Clay (André Holland), a businessman strained by marital discord with his wife Kaya (Zazie Beetz). The two sit in couples therapy with Dr. Amiri (Stephen McKinley Henderson) a name that’s very much not accidental. From the outset, Gaines signals that this will be a self-reflexive, reality-bending adaptation, tinged with magical realism. In an attempt to help Clay reckon with an identity crisis one bound up in his status as a Black man contemplating a political career Dr. Amiri hands him a copy of Baraka’s Dutchman, the very play the film is adapting.

Clay rejects the book outright, but that refusal seems to trigger a chain of strange disturbances. The world around him begins to subtly warp: the background shifts, production design elements quietly mutate. You can feel the film nudging you to notice these changes, even as Clay himself remains largely oblivious. They’re intriguing visual gestures, though the movie never circles back to them in a meaningful way, leaving them to hang like half-remembered dreams. When Clay later boards a subway train, he’s approached by Lula (Kate Mara), a white woman whose flirtation quickly curdles into something more invasive. She knows far too much about him, details no stranger should have access to. Almost immediately, she insists on accompanying him to a party he’s headed to a celebration for his friend Warren (Aldis Hodge), who’s launching a political campaign.

What follows echoes Baraka’s original setup, but with detours. Over the course of a long subway ride and a stop at Lula’s apartment, she alternates between seduction and psychological assault, needling Clay’s deepest insecurities. The film’s absurdist logic makes it difficult for him to escape her orbit; whenever he tries, she reminds him of the power she holds. At one point, she threatens to accuse him of rape if he abandons her, invoking the long, horrifying history of false allegations used to justify violence against Black men and boys history that inevitably calls to mind Emmett Till. It’s a moment crackling with potential, a razor-edged tension that arrives early and then, frustratingly, never fully escalates.

Trapped by circumstance and fear, Clay brings Lula along for the rest of the evening, including the party where she meets both Warren and Kaya. With his marriage and perhaps his physical safety teetering, Clay is forced to endure Lula’s relentless verbal assaults, which masquerade as brutal honesty about race, desire, and self-denial. At the same time, he begins to piece together why these events feel eerily preordained, as though scripted long ago in a stage play that somehow finds its way back into his life through uncanny means.

The problem is that these confrontations only simulate introspection. The film gestures toward the idea of double consciousness, the W.E.B. Du Bois concept describing the fractured self-awareness imposed on Black Americans, but rarely embodies it. Instead, The Dutchman traffics in familiar philosophical talking points about the white gaze, assimilation, and the performance of identity. These ideas are spoken aloud, often eloquently, but they’re seldom dramatized. Despite borrowing the shape and sometimes the actual language of Baraka’s play, the film never forges a convincing thematic or temporal bridge between the radical politics of the Civil Rights era and the comparatively restrained identity discourse of today.

Ironically, this shortcoming exists even as the movie tries very hard to draw a straight line between past and present. It treats the original play almost like a narrative predecessor, positioning itself as a kind of legacy sequel caught between reverence and reinvention. In that liminal space, The Dutchman manages to succeed as a conceptual exercise while faltering as a fully realized thematic statement.

So what, exactly, is the relationship between Gaines’ film and Baraka’s text? The movie doesn’t make you work too hard to figure it out. Its events are both retelling and reverberation, a modern echo of the original drama. Baraka’s play and Anthony Harvey’s stark 1967 film adaptation, which also gets a nod here unfold almost entirely within a single subway car. Gaines repeatedly leaves that confined space, only to keep returning to it, as if unable or unwilling to let it go.

By embracing the idea of narrative recurrence think Stephen King’s The Dark Tower or Hideaki Anno’s recursive Evangelion films The Dutchman comments on itself. It frames Baraka’s story as prophetic, suggesting that the conflicts it depicted never really ended, only changed costumes. Through Dr. Amiri, a clear stand-in for Baraka himself, the film proposes that art might offer insight into these recurring struggles, if not their solutions.

It’s a compelling notion, but also a stiff one. And yes, it plays as dry and academic as it sounds. Clay—his name hinting at pliability is shaped by his environment, yet his inner life is conveyed almost entirely through dialogue. He tells us who he thinks he is; Lula tells us who she believes he really is. What’s missing, even with the expanded settings, is any tangible sense of how Clay actually moves through the world. We rarely see him living, adapting, or resisting in ways that feel organic. He becomes less a person than a symbolic descendant of Baraka’s Clay, distilled into a collection of inherited ideas rather than a fully realized individual grappling with history’s weight in his own distinct way. That flattening extends to the film’s visual flourishes, which hint at depth without ever quite earning it.

When the movie first signals its connection to the play, it does so with obvious stylistic cues: spatial distortions, abrupt lighting shifts, lenses that seem cracked or warped as Clay descends into the subway, like someone stepping into a dream or a trap. You can feel the film trying to tell you that something significant is happening. But beyond a colder, grimier color palette, little actually changes. The mood shifts, but the meaning doesn’t crystallize.

That shallowness mirrors how The Dutchman ultimately engages with Baraka’s work. The temporal overlap is strange and intriguing, a ripple in time, but Gaines and Basir don’t push it further. Aside from a few especially nasty moments of Lula directing her racial hostility toward Black women, the film adds little that feels new. Those provocations are self-aware, but they rarely provoke anything truly raw from Clay. The surreal elements, too, fail to unsettle him in any lasting way. Good surrealism lingers; it gnaws at the soul. Here, the oddities register as intellectual reminders rather than emotional disruptions. Even when familiar faces appear in impossible places, the effect is fleeting, dulled by the film’s compulsion to explain itself.

When The Dutchman finally arrives at conclusions similar to Baraka’s about the necessity and singular power of Black culture and Black artistic expression it feels oddly disconnected from the story that led there. The ideas seem to materialize out of thin air. André Holland and Kate Mara do everything they can with what they’re given, delivering intense, committed performances that hold your attention through dense, talk-heavy scenes. But even the most skilled actors can only do so much when a film demands reinvention without supplying the tools to achieve it.

For a first-time feature director, Gaines shows an instinct for momentum and atmosphere. The film moves briskly and keeps you curious. Yet despite its lofty ambition to enshrine a lineage of Black storytelling across generations it ends up speaking softly about both past and present. What remains isn’t the blistering fury of Baraka’s original, but a cycle of echoes: sound and motion that repeat themselves, suggesting struggle without quite breaking free from it.

Content Breakdown for Parents

Violence & Intensity: There is very little physical violence, but the film carries a strong sense of psychological threat. Characters make disturbing accusations and threats, and there is constant emotional tension rooted in racial power dynamics. A brief moment of violence occurs late in the film, but it’s not prolonged or graphic.

Language: Strong language appears throughout, including frequent use of the F-word and racially charged dialogue. Slurs are not used casually, but racial hostility is expressed verbally in ways meant to unsettle and provoke.

Sexual Content / Nudity: There are sexual conversations, flirtation, and implied sexual situations. Some scenes involve manipulation and coercion, which may be more troubling than explicit content. Nudity is minimal to nonexistent, but sexual tension is a constant presence.

Drugs, Alcohol & Smoking: Characters drink alcohol socially at gatherings. No drug use is depicted.

Recommended Age Range: Ages 17+ only. Even for older teens, this is best viewed with maturity, media literacy, and ideally, the willingness to talk afterward.

Release date January 2, 2026 (United States)

Highly Recommended Movies For Parents

I am a journalist with 10+ years of experience, specializing in family-friendly film reviews.